Averting Nuclear War

Kyungkook Kang, Jacek Kugler, and Yuzhu Zeng

The detonation of the first atomic bomb in July 1945 appropriately marks the beginning of the nuclear era. The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 confirmed that nuclear strikes could impose instant "unacceptable damage." Today, the nuclear peril has re-emerged after a long period of dormancy. Putin has threatened limited nuclear strikes in Ukraine, while the confrontational relationship between the United States and China is escalating toward nuclear polarity. During the 1973 war, Israel deployed ready-to-use nuclear weapons and actively thwarted its neighbors' efforts to build nuclear capabilities. North Korea continues to build its nuclear arsenal, even as its economy collapses. Massive Assured Destruction (MAD) has been superseded by first strike and nuclear warfighting strategies. The prospect of nuclear war is not receding.

After an encouraging period of denuclearization in South Africa, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, the desire to join the nuclear club has resurfaced in Iran, South Korea, and even Japan. At the Reykjavik summit in 1986, Reagan rejected the arms control initiative toward a nuclear-free world advanced by Gorbachev, and the nuclear arms reduction agreements reached have now been abandoned. While early policymakers argued the primary goal of nuclear weapons was to prevent, not wage, a nuclear war. However, our book Averting Nuclear War shows that this nuclear taboo against use sustained by the fear of "unacceptable damage" now stands on a tenuous foundation.

Nuclear postures are not fixed but instead have consistently evolved since 1945. As the USSR achieved nuclear parity, Massive Retaliation (MR) was replaced by Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD), ensuring disproportionately high-cost retaliation against any first nuclear strike. Doubting MAD’s stability, strategists like Kissinger and Wohlstetter persuaded Kennedy that nuclear balance alone could not prevent nuclear conflict when facing a risk-prone contender willing to absorb massive losses, such as China in Korea. From the Kennedy administration onward, warfighting strategies replaced purely retaliatory postures. The Trump administration openly embraced preemptive warfighting, and the remaining nuclear powers have followed the U.S. lead. Nuclear arsenals increasingly reflect warfighting postures, as most nuclear nations have now adopted a forward strategy where nuclear war is possible when fundamental security interests are at stake.

Counterintuitively, despite various deployment options, nuclear practitioners now seemingly agree that nuclear preponderance generates stability in a multi-state nuclear world. Kissinger later reversed his stance, arguing that China and the United States must "convince themselves that the other represents a strategic danger." At nuclear parity, he warned, "...we are on the path to a great-power confrontation" with catastrophic consequences. We show in Averting Nuclear War the proliferation of nuclear weapons, warfighting nuclear capabilities, and power parity will lead to war. Deterrence is only stable when conventional and nuclear preponderance re-emerge.

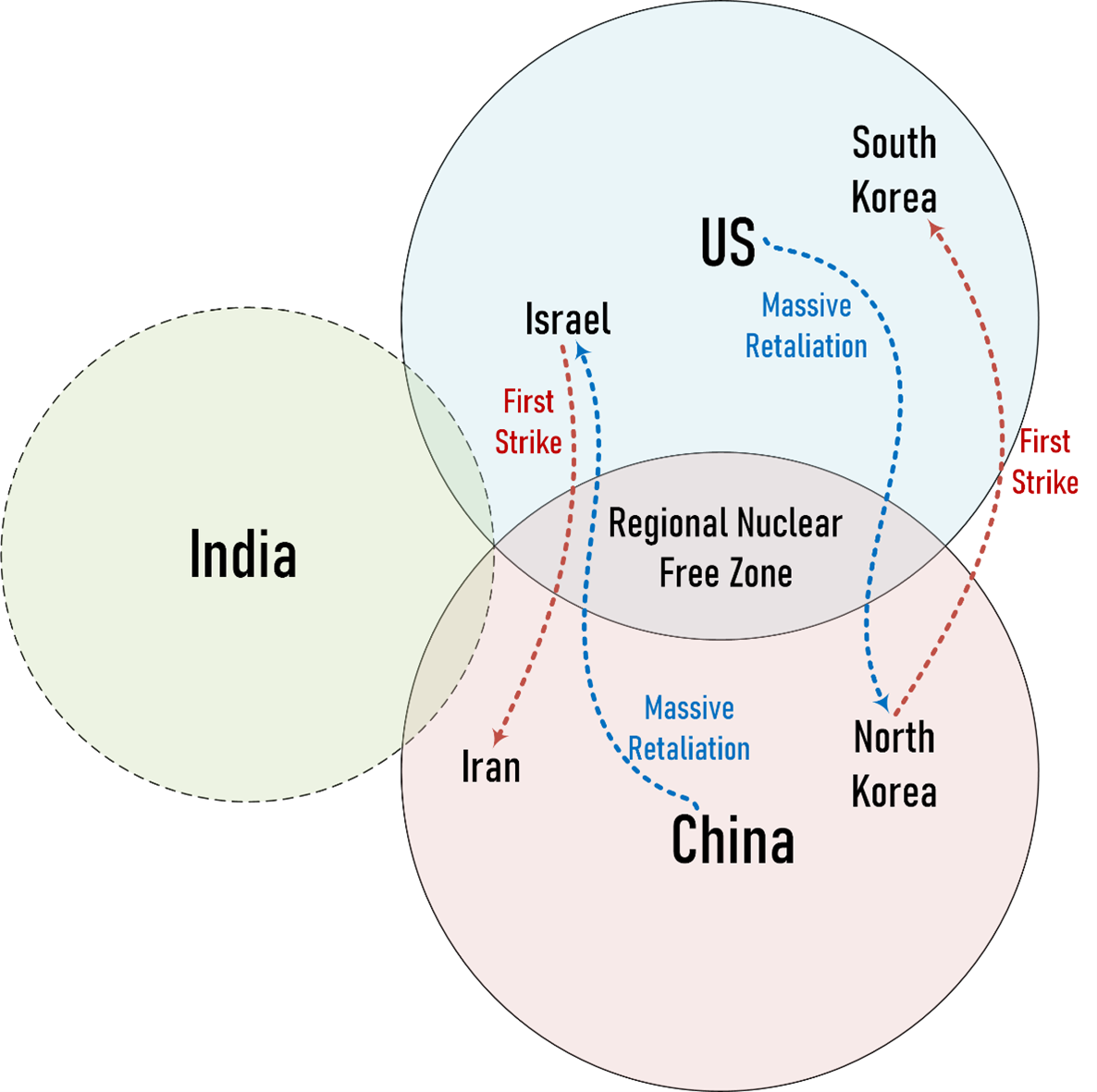

In today’s complex nuclear landscape, achieving nuclear preponderance requires an oligopolistic collusion among nuclear great powers with global reach. Only two countries—the United States and China—have long-term potential to sustain both nuclear and conventional global reach. India will join them in the future but presently lacks global reach. Regional nuclear powers, such as Russia, Britain, France, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea, or non-nuclear states like Iran or South Korea that are considering the nuclear path, can only achieve regional dominance given their more limited conventional capabilities.

We call the collusion between the United States, China, and a future India to prevent nuclear war a “preponderant nuclear oligopoly” (PNO). These nuclear great powers would need to provide—formally or informally—iron-clad, convincing guarantees of immediate nuclear retaliation against any first regional nuclear strike. Only one or all members of the PNO need to act, while the other members commit not to strike back against each other.

The PNO can prevent any regional nuclear confrontation. For example, if Israel, in response to Iran's nuclear advancements, attempts a preemptive nuclear strike against early-stage Iranian nuclear facilities, China would retaliate. At the same time, the United States seeks a post-strike settlement. Conversely, if North Korea were to strike first against South Korea or another region, the United States would retaliate while China seeks a negotiated settlement. More broadly, PNO members would respond with a nuclear strike against any first nuclear strike targeting a regional nuclear or non-nuclear nation. A universal nuclear umbrella would extend to all nations that join a Nuclear-Free Zone or the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The PNO’s extended security commitment is credible because global powers have a significant stake in and benefit most from world stability due to their diverse interests and links across the global structure. As the PNO builds credibility, the incentives for nuclear nations to divest from limited nuclear arsenals and for non-nuclear nations to join nuclear-free zones would far outweigh the benefits of maintaining regional nuclear capabilities. Regardless of fundamental differences in political values, global powers have every incentive to prevent regional nuclear strikes, curb proliferation, and restrict the flow of nuclear weapon technologies. This shared self-interest among global powers would naturally lead them to coalesce into the PNO, thereby preserving nuclear stability.

The PNO cannot prevent conflicts among its oligopoly members. If disputes between China and the U.S. over Taiwan or the South China Sea, or later, border disputes between China and India, were to intensify, the prospects of a global nuclear war cannot be excluded, especially as these global powers reach nuclear overkill and conventional parity. While nuclear strikes by future non-state actors can be minimized through efforts to restrict proliferation, they cannot be entirely averted.

However, what we propose is a radical shift in deterrence posture, moving away from warfighting and nuclear threats toward a preponderant deterrence based on collusion among the few great powers with global nuclear reach. The PNO minimizes the likelihood of limited and regional nuclear war, undermines the rationale for further nuclear proliferation, encourages the decommissioning of existing regional nuclear arsenals, strengthens nuclear-free zones, and bolsters adherence to the Nonproliferation Treaty. In sum, it is imperative to restructure nuclear postures to avert a devastating calamity initiated by minor powers with major firepower.

Kyungkook Kang is Research Specialist in Decision Science at Loma Linda University

Jacek Kugler is Chair Professor at Claremont Graduate University and former President of the International Studies Association

Yuzhu Zeng is Assistant Professor at the Zapara School of Business, La Sierra University